You May Peek at Your Data

Modern sequential inference, applied to election auditing

Horizon Lecture, Australian Statistical Conference 2025

1 December 2025

We love to peek

Peeking 👁️

Planned study: 200 participants

After 40 participants, you decide to do an interim analysis 👁️:

- Large effect estimate

- p-value = 0.03 ⚠️

- “Do we really need more data?”

Could also have checked at 40, 80, 120, 160 participants.

High probability of accidentally seeing p < 0.05 at least once.

P-hacking 🎯

Planned study: 200 participants

After 200 participants, you do the analysis:

- Effect in the right direction

- p-value = 0.08 😕

- “So close…let’s add 20 more participants.”

After 20 more: p = 0.06

And another 20 more: p = 0.049 🎯 → publish!

Similar to peeking, large chance of seeing p < 0.05.

What we teach 🎓

- Choose a fixed sample size

- Perform one pre-specified analysis

- CIs & hypothesis tests nicely calibrated

- Don’t peek!

Statistical “abstinence”

In the real world ⛱️

Abstinence is brittle…

- We check results early

- Data might trickle in slowly

- We adjust analysis plans

- We stop some experiments early

- We continue more promising ones longer

A more liberal approach

Can we design statistical methods that

remain valid even if we analyse the data

whenever we like?

Sequential analysis

Sequential probability ratio test (SPRT)

Developed by Wald (1945)

Birth of sequential analysis

Binary data example

Data (X_i): 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, \dots

Hypotheses: \begin{cases} H_0\colon p = p_0 \\ H_1\colon p = p_1 \end{cases}

Binary data example

Test statistic: S_t = \frac{L_t(p_1)}{L_t(p_0)} = \frac{\Pr(X_1, \dots, X_t \mid H_1)} {\Pr(X_1, \dots, X_t \mid H_0)} = \frac{p_1^{Y_t} (1 - p_1)^{t - Y_t}} {p_0^{Y_t} (1 - p_0)^{t - Y_t}}

Where: Y_t = \sum_{i=1}^t X_i

Binary data example

Binary data example

Stopping rule: \begin{cases} S_t \leqslant \frac{\beta}{1 - \alpha} & \Rightarrow \text{accept } H_0 \\ S_t \geqslant \frac{1 - \beta}{\alpha} & \Rightarrow \text{accept } H_1 \\ \text{otherwise} & \Rightarrow \text{keep sampling} \end{cases}

Error control:

- Type 1 error \leqslant \alpha

- Type 2 error \leqslant \beta

Binary data example

Sample size distribution

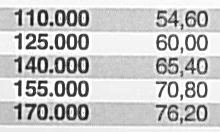

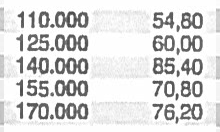

Parameters:

- p_0 = 0.5

- p_1 = 0.7 = p

- \alpha = \beta = 0.1

n = 38 for fixed-n test with same power

SPRT often stops earlier

Benefits 👍

- Safe: can “peek”

- Efficient: small sample sizes

- Can “accept” H_0

- Principled “no decision” is possible

Disadvantages 👎

- Operational planning more complex

- Sample size unknown in advance

- Sample size could be very large

- Only simple vs simple (for now…)

SPRT in general

H_0\colon X \sim f_0(\cdot) \quad \text{vs} \quad H_1\colon X \sim f_1(\cdot)

Test statistic: S_t = \frac{f_1(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_t)} {f_0(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_t)}

Test statistic, with iid observations: S_t = \prod_{i=1}^t \frac{f_1(X_i)}{f_0(X_i)} = S_{t - 1} \times \frac{f_1(X_t)}{f_0(X_t)}

“Tests of power one”

- Set \beta = 0

- Stopping rule:

Reject H_0 once S_t \geqslant 1 / \alpha - Never “accept” H_0

- No type II error (power = 1), but might have n = \infty.

What makes sequential inference “safe”?

Martingale

“Stays the same” on average

Supermartingale 🦸

“Stays the same or reduces in value” on average

Ville’s inequality

Let S_0, S_1, S_2, \dots be a test supermartingale (TSM):

has non-negative terms (S_i \geqslant 0) and starting value S_0 = 1.

For any \alpha > 0, \Pr\left(\max_t (S_t) \geqslant \frac{1}{\alpha}\right) \leqslant \alpha

Tests based on martingales

- S_t should be a test supermartingale (TSM) under H_0

- S_t should grow quickly under H_1

Beyond simple hypotheses

H_0\colon \theta = \theta_0 \quad \text{vs} \quad H_1\colon \theta \in \mathcal{A}

Plug-in strategy: S_t = S_{t-1} \times \frac{f(X_t \mid \hat\theta_t)}{f(X_t \mid \theta_0)} \hat\theta_t = a(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{t-1}) \in \mathcal{A}

Beyond simple hypotheses

H_0\colon \theta = \theta_0 \quad \text{vs} \quad H_1\colon \theta \in \mathcal{A}

Mixture strategy: S_t = S_{t-1} \times \frac{\int_{\mathcal{A}} f(X_t \mid \theta) \, g_t(\theta) \, d\theta}{f(X_t \mid \theta_0)} g_t(\theta) \text{ is a distribution over } \mathcal{A} g_t(\theta) \text{ can depend on } X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{t-1}

Safe inference

SAVI: “safe, anytime-valid inference”

- Stopping rules ⏹️ may depend on the data

- Optional stopping 👁️ permitted

- Optional continuation 🎯 permitted

Anytime-valid CIs, p-values and test decisions.

Review paper: Ramdas et al. (2023)

Election auditing

Acknowledgements 💟

- Michelle Blom

- Alexander Ek

- Floyd Everest

- Dania Freidgeim

- Dennis Leung

- Philip Stark

- Peter Stuckey

- Vanessa Teague

Australian Research Council:

- Discovery Project DP22010101

- OPTIMA ITTC IC200100009

Counting the votes

Counting the votes

Counting the votes

What can go wrong?

- Human error

- Machine malfunction

- Malicious interference

More automation \rightarrow less scrutiny

Election audits

Goal:

- Detect (and correct) wrong election outcomes

Gold standard:

- Full hand count of paper ballots

- Slow & expensive

Alternative: statistics! 📊

- Sample ballot papers, infer the winners

- Fast & cheap – via sequential tests

Two-candidate example

Election: Albo vs Dutton 🤼

p = \text{Proportion of votes for Albo}

\begin{cases} H_0\colon p \leqslant 0.5, & \text{Albo did not win} \\ H_1\colon p > 0.5, & \text{Albo won} \end{cases}

Two-candidate example

SPRT with a plug-in estimator of p:

S_t = S_{t-1} \times \frac{\Pr(X_t \mid \hat{p}_t)}{\Pr(X_t \mid p = 0.5)} \hat{p}_t = h(X_1, \dots, X_{t-1}) \in (0.5, 1]

“ALPHA supermartingale” (Stark 2023)

Preferential elections

Voting

Rank the candidates in order of preference.

Examples:

(1) Lynne, (2) Ben, (3) Ian

(1) Ben, (2) Lynne, (3) Ian

(1) Ian, (2) Lynne

(1) Ben

Counting

Iterative algorithm:

- Eliminate least preferred candidate; redistribute their votes

- Last candidate standing is the winner.

This produces an elimination order.

Example:

- [Ian, Ben, Lynne]

Auditing challenge

H_0 includes all elimination orders with

alternative winners (“alt-orders”).

k candidates \Rightarrow \sim k! ballot types

k candidates \Rightarrow \sim k! alt-orders

Challenges:

- High-dimensional parameter space

- Complex boundary between H_0 and H_1

Auditing strategy

- Decompose H_0 into simpler, 1-dimensional statements

- Test each statement separately

- Combine test results into a single decision

Simple statements

Example:

“Lynne has more votes than Ben assuming that only

candidates in the set \mathcal{S} remain standing.”

Equivalent to a two-candidate election.

Can test using ALPHA.

Hypothesis decompositions

Unions: H = H^1 \cup H^2 \cup \dots \cup H^m \text{Reject every } H^j \Rightarrow \text{Reject } H

Intersections: H = H^1 \cap H^2 \cap \dots \cap H^m \text{Reject at least one } H^j \Rightarrow \text{Reject } H

Adaptive weighting (for intersections)

Base TSM: for H^j

S_{j,t} = \prod_{i = 1}^t s_{j, i}

Intersection TSM: for H

S_t = \prod_{i = 1}^t \frac{\sum_j w_{j, i} \, s_{j, i}}{\sum_jw_{j, i}}

The weights w_{j, i} can depend on data up until time i - 1.

How to choose the weights w_{j, i}?

Weighting schemes

Scaling up

k! alt-orders

\rightarrow 💥 explosion of decompositions & intersections

Use combinatorial optimisation methods.

\rightarrow see tomorrow’s talk 🎤

(Tue 11:30am, Experimental Design / Theory)

Applications & challenges

Where is sequential analysis used?

- 🗳️ Election auditing

- 💻 A/B testing & online experimentation

- 🤖 Online decision-making

- 🔬 Drug safety surveillance

- 🦠 Public health surveillance

- 🧬 Clinical trials

- 🏭 Quality control

- 💳 Fraud detection

When to use anytime-valid methods

- Early decisions are valuable

- Data arrive sequentially

- Analysis plans can evolve flexibly

- Want robustness against “peeking”

Research frontiers

Many open problems!

- Improving efficiency (“power”)

- Complex, high-dimensional models

- Regression/GLMs

- Beyond iid/exchangeable data

- Connections with Bayesian approaches

- 🖥️ Software

- 📖 Teaching materials

Conclusions

What we used to teach

- Peeking is dangerous

- Fixed sample sizes are safe

- Stick to the plan

What we now know

- Peeking can be safe

- Modern sequential methods give:

- anytime-valid inference

- flexibility

- robustness to unplanned analyses

Conclusions

Let’s modernise our statistical toolbox.

We can peek, we can adapt, and we can stay valid.

Time for safe stats 🤍, not statistical abstinence.

Questions?

References 📚

Ek, Stark, Stuckey, Vukcevic (2023). Adaptively Weighted Audits of Instant-Runoff Voting Elections: AWAIRE. In: Electronic Voting. E-Vote-ID 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 14230:35–51.

Ramdas, Grünwald, Vovk, Shafer (2023). Game-Theoretic Statistics and Safe Anytime-Valid Inference. Statist. Sci. 38(4):576–601.

Stark (2023). ALPHA: Audit that learns from previously hand-audited ballots. Ann. Appl. Stat. 17(1):641–679.

Wald (1945). Sequential tests of statistical hypotheses. Ann. Math. Stat. 16(2):117–186.

Image sources 🖼️

The coin flipping graphic was designed by Wannapik.

The following photographs were provided by the Australian Electoral Commission and licensed under CC BY 3.0:

The Higgins ballot paper (available from The Conversation) was originally provided by Hshook/Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The photograph of Abraham Wald is freely available from Wikipedia.

The photograph of the 18th century print is freely available from the Digital Commonwealth; the original sits at the Boston Public Library.

Jokes 😄

The “safe stats / abstinence” joke was borrowed from Hadley Wickham.

Appendix

SPRT for binary data

Martingales: origin

Martingales: origin

“Martingales”: 🎲 gambling strategies from 18th century France ♣️

These strategies cannot “beat the house”

\Rightarrow no guaranteed profit

\Rightarrow at best, a “fair” game

Martingales (in mathematics) represent the 💰 wealth over time of a gambler playing a fair game.

Tests based on martingales

Decision rule:

- Reject H_0 if S_t \geqslant 1 / \alpha

- Otherwise keep sampling (or give up)

Ville’s inequality \rightarrow anytime-valid type I error control

Growth rate under H_1 \rightarrow statistical efficiency (“power”)

The SPRT is a martingale

At time t: \mathbb{E}_{H_0} \left(\frac{f_1(X_t)}{f_0(X_t)}\right) = \int \frac{f_1(x)}{f_0(x)} f_0(x) \, dx = \int f_1(x) \, dx = 1

Martingales generalise likelihood ratios.

New concepts & terminology

- E-value

- E-variable

- E-process

- Anytime-valid p-values

- Confidence sequences (anytime-valid confidence intervals)

E-variable

- A non-negative statistic E with: \mathbb{E}_{H_0}(E) \leqslant 1

- Betting analogy: payoff from a $1 bet in a (sub-)fair game

- Statistical interpretation: evidence against H_0

- Large E → strong evidence against H_0

- A realisation of E is an e-value.

E-process

- Similar to a supermartingale, but more general

- Sequence (E_t) with \mathbb{E}_{H_0}(E_t) \leqslant 1 \quad \text{for all } t.

- Betting analogy: accumulated wealth after many fair bets

- Statistical interpretation: accumulated evidence against H_0

- Ville’s inequality applies

- Stop anytime → type I error control

P-values from e-values

P_t = \frac{1}{E_t}

E_t > \frac{1}{\alpha} \quad \Longleftrightarrow \quad P_t < \alpha

- P_t is an anytime-valid p-variable.

- A realisation of P_t is an anytime-valid p-value.

Confidence sequences

Fixed-sample hypothesis test \longleftrightarrow confidence interval (CI)

Sequential hypothesis test \longleftrightarrow confidence sequence (CS)

“E-hacking”

Reanalysing the data with different test statistics (“betting strategies”) and only reporting the best one.

This is not safe stats.

Fundamental principle:

Declare your bet before you play.

Pre-registration is still an important tool.

However, anytime-valid methods retain flexibility even after pre-specification.

USA horror stories

Don’t trust your scanner

Xerox bug 🐛:

Source: https://www.dkriesel.com/

Prerequisites for an election audit

- Trustworthy paper ballots

- Ability to sample randomly from the ballots

Audit outcomes

Possible decisions:

- 🏆 Certify the reported election result

- ⌛ Request a recount of the votes

Consequences:

| Certify | Recount | |

|---|---|---|

| Reported result is wrong | ❌ | ✅ |

| Reported result is correct | ✅ | ❌ |

Audits as tests

| Reject H_0 (certify) | Do not reject H_0 (recount) | |

|---|---|---|

| H_0\colon Reported result is wrong | Type 1 error ❌ | ✅ |

| H_1\colon Reported result is correct | ✅ | Type 2 error ❌ |

Type 1 error = Wrong democractic outcome

Type 2 error = Waste of resources (but no change of outcome)

Australian voting systems 🇦🇺

Instant-runoff voting (IRV)

- Elects a single candidate

- House of Representatives

- Most state lower house elections

Single transferable vote (STV)

- Elects multiple candidates

- Senate

- Most state upper house elections

AWAIRE weighting schemes

How to choose the weights w_{j, i}?

Ideas:

- Largest: Put weight 1 on the largest base TSM so far.

- Linear: Proportional to previous value, w_{j, i} = S_{j, i - 1}.

- Quadratic: Proportional to square of previous value, w_{j, i} = S_{j, i - 1}^2.

- Many more…

Compared about 30 schemes. “Largest” was often the best.

AWAIRE performance