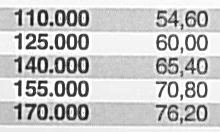

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Elections…Trust?…Verify! ## Statistical audits of election results ### Damjan Vukcevic ### SSA Vic / University of Melbourne public lecture ### 30 March 2022 --- # Collaborators ## USA - Ron Rivest - Philip Stark ## Melbourne - Michelle Blom - Peter Stuckey - Vanessa Teague ## Students - Floyd Everest - Calvin Huang --- # Overview 1. Why? 2. How? 3. More complex elections 4. Australian elections --- class: inverse, center, middle # Why audit? --- # Elections - Foundational for democracy - Can be challenging to run effectively -- ## Elections in Australia - Inclusive - Efficiently run - Highly trusted (...relatively speaking) --- # Two key ingredients 1. Paper ballots 2. Scrutineering -- Old fashioned? Inefficient? -- Pressure to: - Automate, speed up, reduce costs - Replace people with computers --- # USA horror stories [Serious Error in Diebold Voting Software Caused Lost Ballots in California County](https://www.wired.com/2008/12/unique-election/) (2008) [Wisconsin Election Surprise: David Prosser Gains 7,500 Votes After ‘Human Error’ In Waukesha County](https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2011/04/07/david-prosser-wisconsin-supreme-court_n_846431.html) (2011) [Russians hacked 2 Florida voting systems](https://www.politico.com/states/florida/story/2019/05/14/russians-hacked-2-florida-voting-systems-fbi-and-desantis-refuse-to-release-details-1015772) (2019) -- ## Move to electronic systems Rapid computerisation of elections since 2000 presidential election ('hanging chads') Abandoned many previous verification processes --- # NSW iVote failures iVote: electronic voting system used in NSW -- NSW local council elections, Nov/Dec 2021: - System went down for several hours - Many voters were unable to vote -- Also previously: * Encryption flaws discovered by Vanessa and colleagues (Thomas Haines, Sarah Jamie Lewis, Olivier Pereira) --- # Australian Senate elections Ballot papers are handled electronically (for some parts of the process): - Scanned - Digitised - Counted (digitally) -- What could go wrong? -- - Machines are proprietary and closed-source - Scanning and counting not fully open to scrutiny(?) --- # Don't trust your scanner [Xerox bug](https://www.dkriesel.com/en/blog/2013/0802_xerox-workcentres_are_switching_written_numbers_when_scanning): .pull-left[ .center[  ] ] .pull-right[ .center[  ] ] -- Other examples: - Hole-punch filling - Image manipulation attacks -- In the Appendix: - Senate errors experiment --- # Recommendations and changes Jan 2018: Australian National Audit Office [recommended a 'statistically valid audit'](https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/aec-procurement-services-conduct-2016-federal-election) -- Nov 2021: New legislation passed (Assurance of Senate Counting), requiring: * A statistical check of the accuracy of the digital data * Not a 'full' audit (more details at the end) --- # Reasons to conduct an audit Detect inadvertent errors Detect deliberate manipulation Increase confidence in reported result Increase **trust** in our electoral processes --- class: inverse, center, middle # Introduction to election audits --- # Types of audits * Process/compliance audits * Results audits -- - **Ballot-polling** audits - Comparison audits - Hybrid audits --- # Ballot-polling audits Like a standard poll We 'survey' the ballots -- We need: * A trustworthy paper trail (i.e. paper ballots) * A list/record of all ballots * Ability to retrieve specific ballots -- Typically sample **without** replacement ...but can approximate by assuming sampling with replacement --- class: clear, center, middle .font180[Let's do it...] --- class: clear, center, middle  [Alice and Bob 'retired'](https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/09/04/woke-wars-edinburghs-computer-scientists-banned-using-alice/) --- class: clear, center, middle .font180[Let's do it...] Albo vs Scott --- # Inference for sample proportion True vote proportion for a particular candidate (reported winner): `$$p = \Pr(X = \text{Albo})$$` Sample (assume iid, and no invalid votes): `$$X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n \in \{\text{Albo}, \text{Scott}\}$$` -- Sample tally: `$$Y = \text{votes for Albo} = \sum_{i=1}^j \mathrm{1}(X_i = \text{Albo})$$` -- Sample proportion: `$$\hat{p} = \frac{Y}{n}$$` -- Sampling distribution: `$$Y \sim \mathrm{Binomial}(n, p)$$` --- # Binomial distribution (n = 20) <!-- --> --- # Binomial distribution (n = 100) <!-- --> --- # Estimation Suppose we got `\(y = 13\)` out of `\(n = 20\)` sampled ballots. `$$\hat{p} = \frac{13}{20} = 0.65$$` -- `$$\text{95% confidence interval: } (0.41, 0.84)$$` -- What if we got `\(y = 65\)` out of `\(n = 100\)`? -- `$$\hat{p} = \frac{65}{100} = 0.65$$` `$$\text{95% confidence interval: } (0.55, 0.74)$$` --- # Traditional post-election audits Sample a **fixed** number (proportion) of ballots -- ## Example Californian law 1965: 1% of ballots to be checked by hand -- ...and what next? --- # Outcomes ## Possible decisions * 🏆 **Certify** the reported election result * ⌛ Request a **recount** of the votes -- ## Outcomes | | Certify | Recount | |----------------------------|:--------------------:|:--------------------:| | Reported result is wrong | 👎 | ✅ | | Reported result is correct | ✅ | 👎 | --- # Formalisation as a hypothesis test | | Reject `\(H_0\)` (certify) | Do not reject `\(H_0\)` (recount) | |----------------------------------------|:----------------------:|:-----------------------:| | `\(H_0\colon\)` Reported result is wrong | Type 1 error (👎) | ✅ | | `\(H_1\colon\)` Reported result is correct | ✅ | Type 2 error (👎) | -- In our example: `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon p \leqslant 0.5, & \text{Albo did not win} \\ H_1\colon p > 0.5, & \text{Albo won} \end{cases}$$` -- Error rates: `$$\begin{cases} \alpha = \Pr(\text{Type 1 error}) = \text{Miscertification rate} \\ \beta = \Pr(\text{Type 2 error}) = \text{Unnecessary recount rate} \end{cases}$$` --- # Tradition is inefficient -- ## Landslide election Very small `\(\alpha\)` and `\(\beta\)` `\(\Rightarrow\)` Could have used a smaller sample -- ## Close election Large `\(\alpha\)` or `\(\beta\)` `\(\Rightarrow\)` May need a larger sample -- ## A smarter approach? Want to sample **as few ballots as possible**, until we have sufficient evidence --- # Sequential hypothesis test Collect only **enough** samples to make a decision -- <img src="index_files/figure-html/simulated-process-1.png" width="648" /> --- # Sequential hypothesis test .pull-left[ ## Statistics Let `\(X = 1\)` be a vote for the reported winner (Albo), `\(X = 0\)` otherwise. Running tally: `$$Y_j = \sum_{i=1}^j X_i$$` Sample proportions: `$$\hat{p}_j = \frac{Y_j}{n}$$` ] -- .pull-right[ ## Procedure 1. Sample some ballots 2. Calculate test statistic 3. Evaluate stopping rule, and do one of: a) Accept `\(H_0\)` b) Accept `\(H_1\)` c) Insufficient evidence, keep sampling (go to step 1) ] --- # Sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) Developed by Wald (1945) `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon p = p_0 \\ H_1\colon p = p_1 \end{cases}$$` -- Test statistic (likelihood ratio): `$$S_n = \frac{\Pr(X_1, \ldots, X_n | H_1)} {\Pr(X_1, \ldots, X_n | H_0)} = \frac{p_1^{Y_n} (1 - p_1)^{n - Y_n}} {p_0^{Y_n} (1 - p_0)^{n - Y_n}}$$` -- Stopping rule: `$$\begin{cases} S_n \leqslant \frac{\beta}{1 - \alpha} & \Rightarrow \text{accept } H_0 \\ S_n \geqslant \frac{1 - \beta}{\alpha} & \Rightarrow \text{accept } H_1 \\ \text{otherwise} & \Rightarrow \text{keep sampling} \end{cases}$$` -- This controls type 1 error, `\(\alpha\)`, and type 2 error, `\(\beta\)` Is **most efficient** (smallest mean sample size) for the given hypotheses --- # Example ## 2008 USA presidential election Winner's vote proportion = 61% (Obama) Expected sample size = 97 (0.0007% of votes) -- (assuming a hypothetical, single-electorate election) --- # Risk-limiting audits (RLAs) A procedure that does one of: 1. Certify a reported election outcome (if strong evidence in favour) 2. Escalates to a full manual count (otherwise), which reveals the true outcome -- Key properties: * Never changes correct outcomes * Corrects wrong outcomes 'most' of the time (modifiable guaranteed lower bound) -- Limiting risk: * **Risk** = type 1 error * RLAs limit the probability of accepting an incorrect outcome (i.e. control type 1 error) -- The sample size required is variable --- # BRAVO An RLA by [Lindeman, Stark & Yates (2012)](https://www.usenix.org/conference/evtwote12/workshop-program/presentation/lindeman) 'Ballot-polling Risk-Limiting Audits to Verify Outcomes' -- For 2-candidate contests, equivalent to SPRT with: - `\(p_0 = \frac{1}{2}\)` - `\(p_1 =\)` reported proportion (possibly adjusted) - `\(\beta = 0\)` -- Never accept `\(H_0\)` (reported outcome is incorrect), until we have seen **all** of the ballots. -- We can stop sampling at any time and initiate a recount. --- # BRAVO <img src="index_files/figure-html/simulated-process-with-boundary-1.png" width="648" /> --- class: inverse, center, middle # More complex elections --- # 'First past the post' <!-- --> --- # Parameter space with `\(k\)` candidates Parameter space: `\((p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_k)\)`, with `\(p_1 + p_2 + \cdots + p_k = 1\)` Assume candidate 1 is the reported winner Hypotheses: `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon \; p_1 \leqslant p_j, & \text{for some } j > 1 \\ H_1\colon \; p_1 > p_j, & \text{for all } j > 1 \end{cases}$$` --- # Parameter space with 3 candidates .center[ <!-- --> ] --- # Pairwise comparisons Consider each (winner, loser) pair Need to test: `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon p_\text{winner} \leqslant p_\text{loser} \\ H_1\colon p_\text{winner} > p_\text{loser} \end{cases}$$` -- Test all such pairs, until **every** `\(H_0\)` is rejected -- Can use the **same** sample for all tests No 'multiple testing' penalty! --- # Risk limit with multiple comparisons Certify only if *every* `\(H_0\)` is rejected -- Type 1 error (risk) is bounded by the error for a single comparison -- For any `\(j\)`: `$$\Pr(\text{reject } H_{01}, \text{reject } H_{02}, \ldots, \text{reject } H_{0m}) \leqslant \Pr(\text{reject } H_{0j})$$` --- # More general elections `\(k =\)` number of **ballot types** Parameter space: `$$\{(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_k) : p_1 + p_2 + \cdots + p_k = 1\}$$` -- Voting rule ('social choice function'): `$$g(p_1, p_2, \ldots, p_k) = \{\text{winning candidates}\}$$` -- Hypotheses for auditing: `$$\begin{cases} H_0 = \{\theta : g(\theta) \neq \{\text{reported winners}\}\}, \\ H_1 = \{\theta : g(\theta) = \{\text{reported winners}\}\}. \end{cases}$$` -- Some challenges: - Parameter space can become very high-dimensional - Some voting rules can be difficult to analyse --- # SHANGRLA [Stark (2020)](https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54455-3_23), with [software](https://github.com/pbstark/SHANGRLA/) contributions from several authors 'Sets of Half-Average Nulls Generate Risk-Limiting Audits' General framework for RLAs -- Decouple into separate problems: 1. Voting rules `\(\rightarrow\)` 'assertions' & 'assorters' 2. Statistical tests `\(\rightarrow\)` canonical form (univariate, nonnegative) -- More details in the Appendix --- # Testing assertions Tests always of the same form `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon \text{assorter mean} \leqslant 1/2 \\ H_1\colon \text{assorter mean} > 1/2 \end{cases}$$` -- Need a distribution-free test for the mean of a non-negative random variable. --- # Martingales Non-negative (super-)martingales Sequence of random variables `\(Z_j\)`, `\(j = 1, 2, \ldots\)`, such that - `\(Z_j \geqslant 0\)` - `\(\mathbb{E}(Z_j) < \infty\)` - `\(\mathbb{E}(Z_{j+1} \mid Z_1, \ldots, Z_j) = (\leqslant) Z_j\)` -- Examples of martingales: * A gambler's fortune in fair game * An unbiased random walk (can be negative, or can stop at 0) --- # Ville's inequality (1939) If `\((Z_j)\)` is a non-negative super-martingale, then for any `\(\alpha \in (0, 1]\)` and all `\(J \in {1, \ldots, N}\)`, `$$\Pr\left(\max_{1 \leqslant j \leqslant J} Z_j \geqslant \frac{1}{\alpha}\right) \leqslant \alpha \, \mathbb{E}(Z_J)$$` -- How do we use it? -- * Construct a `\((Z_j)\)` with mean 1 * Reject `\(H_0\)` when `\(Z_j \geqslant 1 / \alpha\)` for some `\(j\)` * `\(\Rightarrow\)` risk `\(\leqslant \alpha\)` --- # SHANGRLA martingales (old) Kaplan–Markov `$$S_n = \prod_{i = 1}^n \frac{X_i + \gamma}{0.5 + \gamma}$$` Kaplan–Wald `$$S_n = \prod_{i = 1}^n \left(\gamma \left[\frac{X_i}{0.5} - 1\right] + 1\right)$$` KMart `$$S_n = \int_0^1 \prod_{i = 1}^n \left(\gamma \left[\frac{X_i}{0.5} - 1\right] + 1\right) d\gamma$$` --- # ALPHA 'Audit that Learns from Previously Hand-Audited Ballots' `$$S_n = \prod_{i=1}^n \left(\frac{X_i}{\mu_i} \cdot \frac{\eta_i - \mu_i}{u_i - \mu_i} + \frac{u_i - \eta_i}{u_i - \mu_i}\right)$$` -- See [Stark (2022)](https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.02707) for details -- ## Short course Philip will present martingale-based methods in a short course on 12-14 April (dates TBC) Look out for an announcement, or **ask me if interested!** --- # Complications and extensions ## Real-world issues - Invalid votes - Missing ballots - Contest not on ballot - Stratified sampling -- ## Other types of election audits - Comparison - Batch comparison -- (can be handled by SHANGRLA) --- # RLAs in the 'wild' (in the USA)  --- class: inverse, center, middle # Auditing Australian elections --- class: clear, center, middle  --- # Australian voting systems * **Instant-runoff voting** (IRV) House of Representatives, state lower house elections -- * **Single transferable vote** (STV) Senate, state upper house elections --- # STV example  --- # Auditing IRV RAIRE: 'Risk-limiting Audits for Instant Runoff vote Elections' See [Blom et al. (2019)](https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.08804) -- Uses the SHANGRLA framework and a branch-and-bound algorithm (Some details in the Appendix) -- IRV RLA pilot in San Francisco, 2019 --- # Auditing STV? Three strategies: - Use SHANGRLA, by deriving assertions for STV - Develop a Bayesian audit and derive a risk-limit - Derive martingales specifically tailored for an IRV/STV election -- Some progress: - [2-seat STV](https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.09921) * Dirichlet-tree models --- # Dirichlet-tree  --- # Dirichlet-tree for IRV ballots  --- # Recent legislation Nov 2021: **Assurance of Senate Counting** Bill “The Electoral Commissioner must arrange for statistically significant samples of ballot papers to be checked throughout the scrutiny of votes for the election to assure that the electronic data used in counting the votes reflects the data recorded on the ballot papers.” “The Electoral Commissioner must ensure that…at least 5,000 ballot papers in total are checked” [for a typical election] -- Some details vague: - What is **'statistically significant'**? - Which errors will be checked? (What about errors that don't influence the count?) --- class: inverse, center, middle # Join us! --- # Positions available ARC project: *[In for the count: Maximising trust and reliability in Australian elections](https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/NCGP/Web/Grant/Grant/DP220101012)* **Postdoc position** 2 years, full-time [Applications close on 7 Apr](https://jobs.unimelb.edu.au/en/job/908247/postdoctoral-research-fellow) **PhD project** Generous top-up scholarship: up to $10k p.a. [Applications welcome](https://apps.eng.unimelb.edu.au/research-projects/index.php?r=site/webView&id=820) --- class: clear, center, middle .font180[Questions?] --- class: inverse, center, middle # Appendix --- # Senate errors experiment Victorian Senate 2019 <table> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> Mismatches </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Count </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> -- .center[ **Rough** estimate of per-digit error: (0.03%, 0.38%) ] --- # Simulating errors Tasmanian Senate 2016  --- # Example applications of sequential tests - Quality monitoring in manufacturing - Variable-length computer tests of human subjects - A/B testing for websites/online services - Drug/vaccine safety surveillance - Group sequential testing in clinical trials - 'Alpha spending' functions - Meta-analyses that are (expected to be) periodically updated - Election auditing --- # Seeking optimality By definition, RLAs: - Bound the risk (type 1 error `\(\leqslant \alpha\)`) - Never accept `\(H_0\)` (type 2 error `\(= 0\)`) -- **Efficiency** is measured by the required sample size -- Since this is random, we can summarise in various ways: - Mean - 90th percentile --- # SHANGRLA elements - Assertions * Mathematical statements about all ballots in a contest -- - Assorters * Mathematical functions on ballots: `\(b \mapsto h(b) \geqslant 0\)` * Correspond to assertions * Assertion is true `\(\Leftrightarrow\)` assorter mean `\(> 1/2\)` -- - Statistical tests are all of the same form: `$$\begin{cases} H_0\colon \text{assorter mean} \leqslant 1/2 \\ H_1\colon \text{assorter mean} > 1/2 \end{cases}$$` --- # Example: Albo vs Scott * 2-candidate contest * Reported winner: Albo -- Assertion `\(\quad p_\text{Albo} > p_\text{Scott}\)` -- Assorter - Albo `\(\mapsto 1\)` - Scott `\(\mapsto 0\)` - Invalid vote `\(\mapsto 0.5\)` --- # Example: Hesse local elections  --- # Example: Hesse local elections Party-list proportional representation contest - Can vote for **multiple** candidates - Can give **multiple** votes for each candidate -- Need **pairwise difference** assertions: `$$p_A > p_B + d$$` -- An assorter for this: `$$h(b) = \frac{b_A - b_B - d \cdot b_T + m_\mathcal{L} \cdot (1 + d)} {2 m_\mathcal{L} \cdot (1 + d)}$$` -- See [Blom et al. (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86942-7_4) for details --- # RAIRE assertions Two types of assertions: 1. Candidate `\(i\)` has more first-place ranks than candidate `\(j\)` has total 'mentions'. 2. After a set of candidates `\(E\)` have been eliminated from consideration, candidate `\(i\)` is ranked higher than candidate `\(j\)` on more ballots than vice versa. -- Branch-and-bound algorithm to optimise the set of assertions. -- RAIRE assertions provide only *sufficient* conditions, but not *necessary* conditions. --- # RLAs in the 'wild' (in the USA) Endorsed by: - National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine - American Statistical Association - PCEA, LWV, CC, VV,... -- Statewide use in: - Colorado since 2017 - Alaska, Kansas, Wyoming since 2020 -- ~60 pilot audits across 17 states Legislated in 11 states --- # Auditing via Bayesian inference Back to Albo vs Scott... `$$p = \Pr(X = \text{Albo})$$` Specify a **prior distribution** on `\(p\)`, e.g. uniform `$$f(p) = 1, \quad p \in [0,1]$$` -- Data + prior `\(\rightarrow\)` **posterior distribution** on `\(p\)` -- 'Upset probability': `$$\Pr(H_0 \mid X_1,\ldots,X_n)$$` -- Certify election if upset probability is low enough `$$\Pr(H_0 \mid X_1, \ldots, X_n) < v$$` --- # Bayes factor Can reformulate in terms of the **Bayes factor** (BF) -- `$$S_n = \frac{\Pr(X_1, \ldots, X_n \mid H_1)} {\Pr(X_1, \ldots, X_n \mid H_0)} = \frac{\int_{0.5}^1 p^{Y_n} (1 - p)^{n - Y_n} f(p) dp} {\int_0^{0.5} p^{Y_n} (1 - p)^{n - Y_n} f(p) dp}$$` -- Certify election if `\(S_n > h\)` -- (Note similarity to the SPRT) --- # Correspondence with the SPRT Choose the following prior: `$$f(p) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}, & \text{if } p = p_0 \\ \frac{1}{2}, & \text{if } p = p_1 \\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$` `\(\Rightarrow\)` same as the SPRT -- Also, can express some Bayesian quantities as martingales -- Provides a unified perspective --- # Some recent work For ballot-polling audits of 2-candidate contests with no invalid votes: * Benchmarked several methods * Bayesian audits are risk-limiting See [Huang et al. (2020)](https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.08536) for details --- # Performance comparison example <img src="index_files/figure-html/sample-size-comparison-1.png" width="648" /> --- # Properties, not dichotomies 'Bayesian' and 'risk-limiting' are not mutually exclusive -- But... * Upset probability `\(\neq\)` risk limit --- # Bayesian audits for complex elections Just follow the 'recipe'? -- * Specify the model * Certify election if upset probability is low enough `$$\Pr(H_0 \mid X_1, \ldots, X_n) < v$$` -- Some challenges: * Calculations can get involved * Need to choose a sensible prior * Not necessarily risk-limiting --- # Open questions Which voting rules cannot be encoded as assertions? For which voting rules is there: - a **sufficient** set of assertions? - a **necessary and sufficient** set of assertions? Are all sets of necessary and sufficient conditions equally expensive to audit? Are any voting rules intrinsically harder to audit than others? Are there optimal tests for testing SHANGRLA assertions, for various types of elections? Are Bayesian audits risk-limiting for more complex voting rules? If so, when can we easily calculate the maximum risk and calibrate the audit? How does a 'direct' inference compare (in terms of efficiency) to assertion-based approaches?